Until November 4, the Edge Gallery in Bath is hosting an exhibition of the groundbreaking work of the Turner Prize winning collective Assemble, who have staged a show along with the artist Simon Terrill. The exhibition reflects upon the influential work of Alison and Peter Smithson. The Smithsons were some of the most important architects in post-war Britain and are often associated with the Brutalist Movement, which focuses on the use of concrete and repetitive forms often used in large housing blocks.

The Smithsons were part of the Independent Group, a collection of artists, architects, and writers who wanted to challenge cultural modernist approaches. The group included artists Nigel Henderson and Eduardo Paolozzi, who were also hugely influential to the work of Assemble. This new exhibition at Edge Gallery exhibition is a tribute to the Smithsons show, ‘Parallel of Life and Art’ from 1953.

Candid Magazine's Cara van Rhyn sat down with Jane Hall, one of the founding members in 2010 of Assemble to discuss the latest project.

Cara van Rhyn: Tell us about your installation ‘The Ostrich and the Kipper’, which is part of the Parallel (of Life and) Architecture exhibition.

Jane Hall: So, the name, ‘The Ostrich and the Kipper’, comes from part of the dialogue in the film ‘The Smithsons on Housing’ which they made as a BBC documentary while they were building Robin Hood Gardens. The ostrich relates to Alison Smithson describing Britain as a country full of ostriches, and Peter Smithson describing Robin Hood as an unfolded kipper.

CvR: Did you take inspiration solely from the Smithsons for this project?

JH: The idea of the exhibition is to draw attention to the more surrealist influences on the Smithsons’ work and how their practice evolved from the art movement. How they emerged from the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in the early 1950s, and particularly how they were influenced by their collaboration with Nigel Henderson and Eduardo Paolozzi.

So, we looked at this film that essentially shows the Smithsons in their formal element talking about social housing in the UK, but when you start really listening to the language that they use, it reveals other references and influences that have been overlooked in the historiography of their work. In this exhibition, we wanted to explore the way in which their characters and their collaboration with artists – Henderson and Paolozzi – influenced their work.

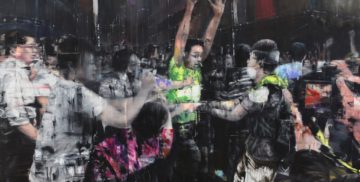

Parallel (of life and) Architecture, at Edge Gallery, Bath. Image courtesy the artists.

CvR: How was Simon Terrill involved in this exhibition?

JH: Simon Terrill and I kind of re-enacted their relationship. The Smithsons produced two exhibitions, Parallel of Life and Art in 1953 and Patio and Pavilion in 1956, both of which were done against the backdrop of the Independent Group.

However, they stated that they were independent of the Independent Group, so this marked the break away from the art movement around the ICA at the time. We began by just working through a process of Simon coming to Assemble and talking to us, looking at how they used image and collage and juxtaposition, all the influences and tropes from their film, and what they said and their own work to start evolving work that reflected some of these practices.

CvR: How did those kind of influences and collaborations manifest themselves in your work?

JH: We began by making ceramic heads, inspired by Eduardo Paolozzi, as a way for us to start using our hands and make something whilst we began talking about the show. The ceramic heads that are dotted around the exhibition are the trace of our conversations – the physical remnants of time that we spent.

So, they obviously don’t look anything like Eduardo Paolozzi’s heads, but we began trying to evolve a process of automation and making them and the way Henderson and Paolozzi would observe and make marks and use things of the everyday that they saw around them in this post-war context. Henderson described this time as ‘real life surrealism’ in that this is the kind of break with pre-war surrealism they didn’t need anymore because life itself was weird enough after [the war].

The urban context and the way people were living were completely affected by war which was this sort of bizarre event that had affected everyone’s lives.

We were talking about those ideas and their processes whilst making these heads and about character and the difference between the physical structures and the ephemeral ones.

(Left) Jane Hall and (Right) Simon Terrill. Parallel (of life and) Architecture, at Edge Gallery, Bath. Image courtesy the artists.

CvR: How does the Smithsons’ Robin Hood Garden play a role in your work?

JH: We did a few walks around Robin Hood after it’s been demolished, and we talked about what trace it will leave on the site and about having a fragment of Robin Hood somehow in the exhibition. And so, we have, in the centre of the room, a 1:1 scale reproduction of part of the façade of Robin Hood with a very British sort of white net curtain behind it.

The Smithsons talked about Britishness so much and about the everyday, so while they evolved Brutalism with a high modernism, actually they’re relating it back to a weird colloquial Britishness that they were embracing, which went against what was being churned out at the time.

So, we wanted to have that juxtaposition in the physical installation with the hardness of the concrete wall, the façade, and the domestic net curtain on which we project an image of Alison and Peter. The image is this really nice moment from the housing film where Peter is unfolding his hands, describing Robin Hood as a kipper and Alison is holding bits of found ceramics. So, this thing of them with their hands describing a process that they were discovering whilst working with Henderson and Paolozzi and how that relates to Robin Hood.

We carried through this idea of using collage and juxtaposition of materials and imagery, which is what the Smithsons did with Henderson and Paolozzi in both exhibitions. Tried to create a setting that might evoke a feeling or a sense of what fragmentation or damnation might mean in relation to Robin Hood, but also in terms of making processes.

CvR: Hence the sand as well?

The sand, and there’s some aluminium sheets that are propped up, are a reference to ‘Patio Pavilion’ which was this whole idea about the central qualities of space that someone might need. Their patio – which is the sand, their physical space – and the pavilion is their shelter and then a view of the sky. They put the aluminium sheet around their exhibition to reflect the presence of the visitor back into space so you are placed back into it. So, we wanted to juxtapose some of these materials.

We started describing our exhibition as a sort of exploded ‘Patio and Pavilion’. If you took their shows and tried to deconstruct them, what are the essential elements and what do they mean?

Then, if you try and put them in a contemporary context with work done by other artists, how does it relate or change?

Parallel (of life and) Architecture, at Edge Gallery, Bath. Image courtesy the artists.

CvR: What is your collage piece about and what inspired it?

We have a big collage which references Henderson’s ‘Head of a Man’ collage, which was in ‘Patio and Pavilion’. He described using imagery from things he was interested in at the time, like bicycle wheels and shoelaces. So, we used the same technique of building up an image of a body but using images taken from Google searches of stuff that the Smithsons say in the film. Ostriches, cabinets, kippers, gondolas from Venice.

It tries to unite the Paolozzi reference with Henderson in a new ‘Head of a Man’. And it’s opposite in the room to a big photo of Robin Hood. It’s an aerial shot that’s been fragmented by altering the code of the TIFF file. Each JPEG has a code that you can access on the computer and it’s just text code, so if you put other text in and save it, the image goes really weird.

You don’t know how it’s going to glitch. We added a sentence to the TIFF file about ruins that Alison says which is, ‘you never know when a bit of ruin is going to come in handy’. We wanted to use a more modern notion of collage and juxtaposition and just see what happens. Everything [in the exhibition] links together, but the room itself is supposed to have a kind of weird eerie feel, which in a way is what the Smithsons did with both ‘Parallel of Life and Art’ and ‘Patio and Pavilion’.

We don’t want to make any claims on what the work is, we’re just really interested to know what people get from being in the space and whether it will conjure different ideas.

These heads are just silly, but we’ve gone somewhere with the collage. There are fragments of starting points and end points dotted throughout the exhibition, so the whole room is really about process. Which is what ‘Parallel of Life and Art’ is about.

CvR: What is it like working in a group like Assemble?

In Assemble, the good thing is that we are all driven by projects with interesting processes and research. We never really start with the brief; we always question the brief and rewrite it before we do something in order to begin.

CvR: What was the brief for this project?

JH: We didn’t have one! This one was interesting as it gave us space to do open ended research. A lot of our process and the way we work together is through making things.

CvR: In a way, you’ve focused on the human side for this exhibition?

JH: Totally, the sociology of it was the interesting side and the Smithsons talked about themselves as anthropologists and outsiders and I suppose the approach is similar to what Assemble does. But they had a really interesting free and weird way of going about it.

CvR: It’s quite fascinating watching them, they’re quite unexpected!

JH: They’re really off-putting! And that’s what we’ve been worried about doing this exhibition, whether if we focus too much on character we’re somehow not portraying them in the best light. But we don’t want to not be critical, so I think it’s just drawing attention away from seeing them as ridiculous and posh 70s elitist architects, and understanding the weirdness and humour and that they probably don’t take themselves that seriously. She’s wearing a bright silver jacket for god sake! The idea is not to historicize them as a weird product of their time.

Parallel (of life and) Architecture, at Edge Gallery, Bath. Image courtesy the artists.

CvR: What are you working on at the moment?

JH: I’m writing a PhD about the Smithsons in comparison to a Brazilian architect, Lina Bo Bardi. They’re both venerated as these genius architects and that’s a big problem in practice. Globally, you have the big superstar architects and the reaction to that is this alternative practice of grassroots and community. Assemble has always spoken about participation and social agenda, which we’re interested in, but we’re not in principle. I think when you try to apply practices to already marginalised groups, you’re just reinforcing marginalization.

CvR: So, this exhibition isn’t linked to the Independent Group at all?

JH: I think what the Smithsons were amazing at doing was placing themselves as outsiders, and always being flux and fluid between an established centre which to them was the Independent Group and the ICA. That’s why I think it’s not an Independent Group exhibition, this is an example of them pushing away from it. And it’s those processes that are interesting rather than alternative techniques. For me anyway, my PhD is about the role of the architect and how to not write yourself out of the process, which is the tendency with this discourse.